To say that our band spends a significant amount of its time trying to copy Michael Jackson’s Thriller would be quite accurate. There are two reasons why. First, the songs. Thriller is a pop music masterclass. Each song is a musical iceberg–on the surface sits deliciously effortless ear candy, but underneath lies a brilliantly crafted […]

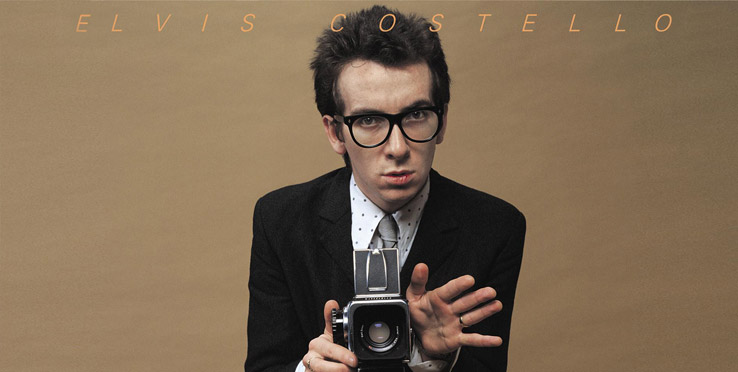

It might have been easy to overlook an album like This Year’s Model early on. After all, here was a set of songs that typified the insurgent attitude of punk rock in its ignominious heyday. It was the work of a petulant young upstart clearly determined to upset the pop cart — and possibly the […]

Story by Brittney McKenna Looking back over the last few decades of popular music, there are only a handful of albums that serve as true landmarks, points on a timeline that elucidate our musical lineage and say, “Hey, this is how we got here.” Many of these albums display a marked departure from the artistic […]

Alright. I’ll come clean. I’ve never been an Elton John fan. In fact, it was my mom who turned me on to the guy. Before my sweet mother introduced me to Tumbleweed Connection, I’d only invested loosely in building up my EJ catalog. It was all a tad sensational for my blood. I believe I […]

I don’t need to tell you anything about Johnny Cash. That’s probably the greatest testament to any artist’s legacy — that their life is elevated to the stuff of myth. The problem with the mythological “Man In Black,” is that we forget all the ways he was just like us, the very reasons he was […]

Dearly Beloved, There is no one like Prince. No one. I think you could make a list of things Prince has done that no one else in the world has ever done or ever could do. You can’t find him on YouTube (he has a team that takes down any footage of him). He’s not […]

Okay. By now, you know what we do. But let’s review quickly: We hand-select the finest albums, match the songs with the best of local acts who collectively cover the record head to toe. We pair all that with a thematic food or beverage and, in short, put on a show that is always memorable. […]

Michael Jackson: Thriller No album, movie, or book should ever have to live up to the expectations attached to the label “biggest selling of all time.” Luckily for Michael Jackson’s Thriller, that moment has passed and it’s just a matter of time before the same is true for James Cameron’s Titanic (the Bible, however, will have to deal […]

There are few stylistic changes more jarring than the one Bruce Springsteen made between 1982’s Nebraska and 1984’s Born in the U.S.A. The first is essentially an album of demos, recorded without the E Street Band; the second is as pop-oriented as “the Boss” ever got, with the addition of synthesizers and bright, radio-friendly arrangements. […]

We are so excited to announce that our very own Micah Dalton is releasing his album “Blue Frontier” on March 13. Make sure to check out the Facebook announcement for more details, and mark your calendars to purchase a copy!