By: Brenda Nicole Moorer I come from a long line of performers. My grandfather and his brothers formed the group The Esquires in the ’60s and won two gold records. They toured the world and supported their families. I still hear their songs in the grocery store sometimes. My father was a singer and piano […]

In a nutshell Thriller is the most influential record of my time. I grew up in a very strict, religious home & Thriller was the only “secular” album my mom would allow me to have. The year was 1983: The Jackson Five are performing at Motown’s 25th anniversary, and I’m glued to the TV. Toward […]

In a nutshell Thriller is the most influential record of my time. I grew up in a very strict, religious home & Thriller was the only “secular” album my mom would allow me to have. The year was 1983: The Jackson Five are performing at Motown’s 25th anniversary, and I’m glued to the TV. Toward […]

To say that our band spends a significant amount of its time trying to copy Michael Jackson’s Thriller would be quite accurate. There are two reasons why. First, the songs. Thriller is a pop music masterclass. Each song is a musical iceberg–on the surface sits deliciously effortless ear candy, but underneath lies a brilliantly crafted […]

When Creedence Clearwater Revival released their third album, Green River, in August of 1969, the nation’s mood was a somber one. With the Vietnam War raging on and the wounds from the Civil Rights struggle still fresh, John Fogerty’s title track declaration that the “world [was] smolderin'” was something of an understatement, a sentiment that […]

Sade – Love Deluxe In 1992, the musical landscape appeared to be suffering from a mild case of schizophrenia. Where there had once been clear and defined lines separating music genres from one another, those lines began to blur at an unprecedented rate as R&B, hip-hop, rock, jazz and even country began bleeding into one […]

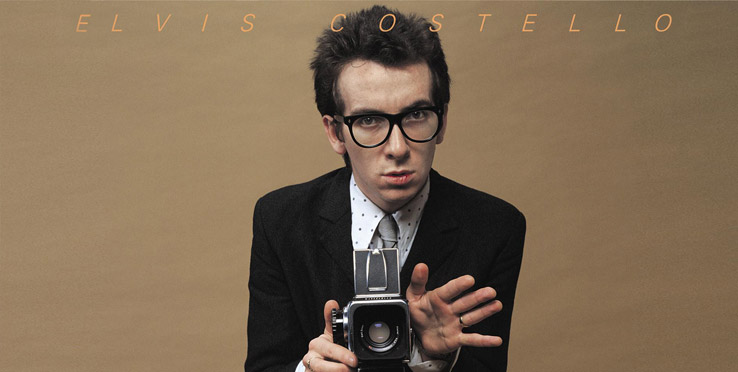

It might have been easy to overlook an album like This Year’s Model early on. After all, here was a set of songs that typified the insurgent attitude of punk rock in its ignominious heyday. It was the work of a petulant young upstart clearly determined to upset the pop cart — and possibly the […]

ATL Collective’s greatest hits Atlanta’s ongoing album-performance project uncovered by Kevin Forest Moreau Frustrated by a general lack of cohesion in the Atlanta music scene and decreasing interest in full-length albums, David Berkeley and Micah Dalton formed the ATL Collective in 2009, hoping to spark a sense of collaboration among local and national acts, and pay […]

Story by Brittney McKenna Looking back over the last few decades of popular music, there are only a handful of albums that serve as true landmarks, points on a timeline that elucidate our musical lineage and say, “Hey, this is how we got here.” Many of these albums display a marked departure from the artistic […]